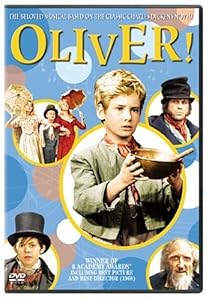

Cover of Oliver!I'm not really certain what I was thinking when I decided that this would be the next book I would read. It's been many years--decades even--since I last read a Charles Dickens book: Great Expectations. I don't remember how old I was, but I suspect I was in my late teens. That book was really great, but it ended with a great disappointment, which has somehow clung onto me since and perhaps prevented me from picking up another of his novels.

Cover of Oliver!I'm not really certain what I was thinking when I decided that this would be the next book I would read. It's been many years--decades even--since I last read a Charles Dickens book: Great Expectations. I don't remember how old I was, but I suspect I was in my late teens. That book was really great, but it ended with a great disappointment, which has somehow clung onto me since and perhaps prevented me from picking up another of his novels.At one place where I worked, there was a retelling of the Oliver Twist book for kids. However, in retrospect, it had as much to do with the original story as the original Beowulf has with any of the poor Hollywood imitations.

Oliver Twist is a book which initially centres around a young boy, Oliver Twist, but later as the story unravels, becomes less and less about him. There is a certain amount of social commentary which I believe Dickens was trying to make. The setting wherein Oliver initially grows up is horrific. It is a 'workhouse' where children are raised. Those whose hands these orphans have been placed skim off of what little charity was afforded them, and consequently malnutrition and death often stalk the young. Oliver manages to escape this condition, only to fall into an apprenticeship which somehow leads him into another unsavoury position, which when he escapes he runs into the main villainous characters of the story.

Herein begins some of the problems which I had with the story. However, before I go there, I want to backtrack to an interesting thing that I noticed: Oliver's superb mastery of the English language. He uses it quite properly and well. This contrasts with those around him. Later on in the book, it is revealed that he came from a middle class family. Is the suggestion that blood is what educates a tongue? Those around him, both children and adults, are not as gifted as he is. There is really no education mentioned at all. So, where did he learn the language?

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaIn any case, he escapes his apprenticeship and runs headlong into the care of a criminal family which consists of an old Jew, Fagin. Over-and-over, he is referred to as the Jew. This character may have been already described by Shakespeare in his Merchant of Venice which had its own crusty, greedy, and generally abhorable caricature of a man. Fagin is a man whose greatest interest in Oliver is to seek to pervert his pure heart. He does what he can to convert Oliver into a dishonest thief, and then use his guilt to pervert him to the dark side entirely.

However, Oliver is caught despite not being the boy in particular who was the thief. On the verge of being held guilty, he is rescued by the victim of the theft. He is taken to the victim's home and restored to health (as he was seriously malnourished and affected by a fever). Coincidentally, this man is connected to Oliver's mother, and he is identified as being too much like his deceased mother for it to be a coincidence. He is then sent on a mission, but intercepted by the criminal gang and put back into the ruthless care of Fagin.

Fortunately for Oliver, he is loved by the girl, Nancy, who is under the control of a powerful thief, Sikes. When they go off to break into a house, Oliver is shot and wounded by one of the servants. He is left for dead, but is not. He stumbles onto the very house he was aiding in robbing (though to be fair, he was ready to raise the alarm to prevent the robbery), and the women who rule the house take pity on him and restore him to good health. The entire story unravels after his recovery with all the horrors and guilty parties identified. His true parentage is also identified.

The end, as it comes, is horrific to the two main villains: Sikes, and Fagin (the Jew). Sikes, after learning that Nancy was ready to turn him in, murders her most brutally. His guilt at the murder is some of the best writing throughout the story:

He went on doggedly; but as he left the town behind him, and plunged into the solitude and darkness of the road, he felt a dread and awe creeping upon him which shook him to the core. Every object before him, substance or shadow, still or moving, took the semblance of some fearful thing; but these fears were nothing compared to the sense that haunted him of that morning's ghastly figure following at his heels. He could trace its shadow in the gloom, supply the smallest item of the outline, and note how stiff and solemn it seemed to stalk along. He could hear its garments rustling in the leaves, and every breath of wind came laden with that last low cry. If he stopped it did the same. If he ran, it followed—not running too: that would have been a relief: but like a corpse endowed with the mere machinery of life, and borne on one slow melancholy wind that never rose or fell.

At times, he turned, with desperate determination, resolved to beat this phantom off, though it should look him dead; but the hair rose on his head, and his blood stood still, for it had turned with him and was behind him then. He had kept it before him that morning, but it was behind now—always. He leaned his back against a bank, and felt that it stood above him, visibly out against the cold night-sky. He threw himself upon the road—on his back upon the road. At his head it stood, silent, erect, and still—a living grave-stone, with its epitaph in blood.The whole dogged run from his conscience is in vain. He cannot escape his own guilt. Eventually, he cannot escape the anger of the community in which he lived, either. They were bent on his capture and hanging. But, in his attempt to escape, he only manages to hang himself. The funny thing about him, though, was the loyalty and love those closest to him had for him: his dog and Nancy. Nancy, despite feeling keenly the warning of death in every shadow and in illusions which haunted her, could not abandon him despite knowing that her death might very well come from him, and that he was a despicable and unworthy man of love.

Fagin, however, is captured and tried for her murder as a conspirator or facilitator of her death. He is found guilty and sent to be hung. The description of him before he is suffered to be hung is also quite poignant:

As it came on very dark, he began to think of all the men he had known who had died upon the scaffold; some of them through his means. They rose up, in such quick succession, that he could hardly count them. He had seen some of them die,—and had joked too, because they died with prayers upon their lips. With what a rattling noise the drop went down; and how suddenly they changed, from strong and vigorous men to dangling heaps of clothes!

Some of them might have inhabited that very cell—sat upon that very spot. It was very dark; why didn't they bring a light? The cell had been built for many years. Scores of men must have passed their last hours there. It was like sitting in a vault strewn with dead bodies—the cap, the noose, the pinioned arms, the faces that he knew, even beneath that hideous veil.—Light, light!

...

Then came the night—dark, dismal, silent night. Other watchers are glad to hear this church-clock strike, for they tell of life and coming day. To him they brought despair. The boom of every iron bell came laden with the one, deep, hollow sound—Death. What availed the noise and bustle of cheerful morning, which penetrated even there, to him? It was another form of knell, with mockery added to the warning.

The day passed off. Day? There was no day; it was gone as soon as come—and night came on again; night so long, and yet so short; long in its dreadful silence, and short in its fleeting hours. At one time he raved and blasphemed; and at another howled and tore his hair. Venerable men of his own persuasion had come to pray beside him, but he had driven them away with curses. They renewed their charitable efforts, and he beat them off.Horrors are inflicted upon the horrible, while the honourable are restored to honour. The villains are punished most dreadfully, while the victims are brought back to their rightful place within the comforts of the upper-middle class.

I suppose that one might say that I got the happy ending in this novel which I was upset over in Great Expectations. However, perhaps I'm less particular about happy endings. On the other hand, it does feel good to feel good at the end of a feel good ending, doesn't it? The tragedy of all these characters, they say, offers a cathartic reward: the lives of those whose situations are far worse than our own are supposed to make us feel better about our own struggles and situations. I enjoyed the book and recommend it. I am sure that I will read another of Dickens' books, though with far less intervening years between.

No comments:

Post a Comment